This article is written in English for international readers.

This article is written in English for international readers.

I have been diagnosed with a developmental disorder and depression, conditions that render sustained employment exceedingly challenging. Presently, I am exploring strategies for survival, both in practical and psychological terms.

On weekdays, I participate in a mental health program designed to facilitate a return to work. However, this marks my second leave of absence from my current position. Given my personal characteristics, energy levels, and motivation, I anticipate that reintegrating into the same workplace would likely result in a recurrence of previous difficulties.

Amid this period of uncertainty, I encountered a significant interpersonal conflict within the program during the summer. Consequently, I chose to withdraw from the program entirely for approximately two months, initiating a phase of social isolation from August to September 2025.

My daily activities were severely restricted: I ventured only to supermarkets and public exercise facilities. My interactions were limited to weekly visits with my parents. For two months, amid an intense summer heatwave, I existed in near-total seclusion.

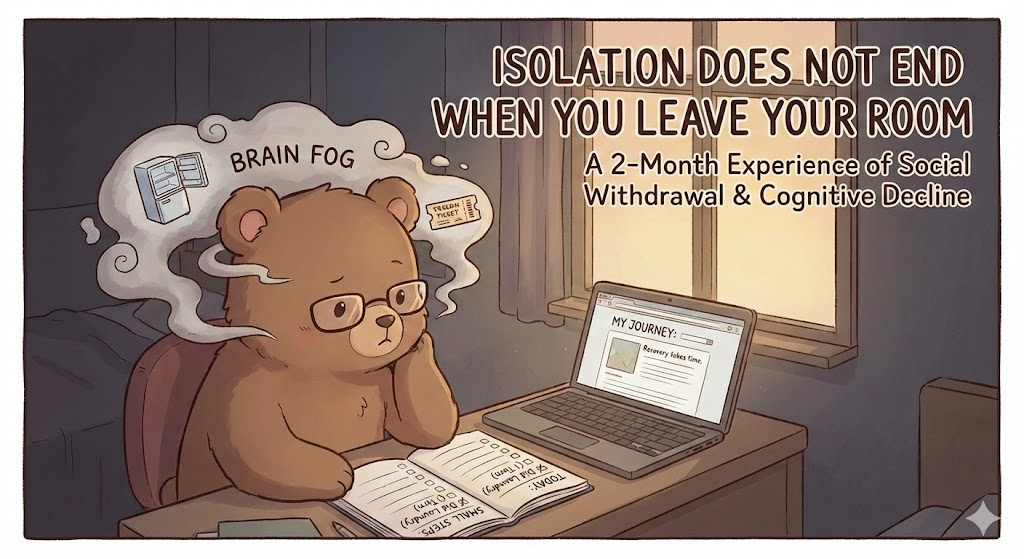

What effects did this have on my physical health, mental state, and behavior?

In this article, I reflect candidly on this experience across three dimensions—physical, mental, and behavioral. This account is intended particularly for individuals who have experienced social withdrawal, those contemplating it, and their families or supporters.

One key conclusion merits emphasis upfront: Recovery does not commence immediately upon ending isolation. Physical and mental challenges often persist well beyond that point. Therefore, proceeding with small, incremental steps is essential.

1. Physical Effects: Unexpected Fatigue Despite Sustained Exercise

Throughout the two months, I did not initially perceive significant physical deterioration. I prioritized sleep, maintaining relatively consistent sleeping and waking schedules. Recognizing the importance of exercise for preserving muscle strength, I continued long-distance walks to distant supermarkets and utilized affordable public gyms for strength training.

However, physical issues emerged abruptly in October, following the end of isolation. Upon resuming the recovery program, I was overwhelmed by profound fatigue. The plan involved a gradual increase in participation—from mornings only, to mid-afternoon, and eventually full days. Yet, I arrived at the clinic already exhausted.

This fatigue extended beyond mere loss of stamina. Despite regular exercise, prolonged indoor confinement evidently contributed to actual physical decline. Compounding this was psychological fatigue, later identified as "easy fatigability"—a mental exhaustion stemming from resistance to social environments. Merely approaching spaces inhabited by others triggered intense internal resistance. The disparity between remaining at home and engaging in social settings proved far greater than anticipated.

Notably, the extreme summer heat may have mitigated some psychological harm. Living in a northern region where I previously didn't feel the need for air conditioning, the heat was so intense this year that I felt it was a necessity. I directed my mental resources toward heat mitigation strategies, such as taking cold baths and rotating ice packs around my neck. Confronting an immediate physical threat left scant capacity for abstract anxieties about the future. Paradoxically, this imminent danger subdued longer-term fears.

2. Mental Effects: Cognitive Decline and Fatigue-Induced Inaction

In retrospect, the isolation itself did not feel intolerable. Individual variations exist, but over two months, I experienced no acute sense of urgency or panic.

The most severe issue was cognitive decline. I frequently sensed a fog enveloping my mind. With interpersonal interactions nearly absent, mental stimulation plummeted. Visual media and written content proved insufficient for me. I realized that a certain degree of social engagement is necessary for my cognitive functioning. While social interaction is stressful, stress also serves as stimulation. To sustain mental capabilities, a moderate level of stress appears indispensable.

After two months of low-stress existence, the consequences manifested upon resuming social activities in October. In addition to physical fatigue, mental exhaustion intensified. This manifested as "easy fatigability," a condition where the mind readily perceives situations as overly taxing. This fatigue directly impeded my capacity for action.

I became capable of only one task per day: "I took a walk—that's all." "I did the laundry—that's all." I consciously focused on counting what I could do—like "I did the laundry today" or "I went shopping today"—rather than focusing on what I couldn't accomplish.

My ability to handle tasks diminished markedly. These cognitive impairments did not resolve swiftly. Even after restarting blogging and program participation, issues such as forgetting to lock doors or misplacing tickets persisted for some time. The damage from stimulation deprivation affects the brain profoundly, requiring extended periods for recovery.

3. Behavioral Effects: Escalating Failures and the Output Born from Crisis

The most alarming aspect was the rise in failure-prone behaviors attributable to cognitive decline.

- Leaving my backpack open while outdoors (once)

- Forgetting tickets at train gates (three times)

- Repeatedly returning home due to anxiety about locking doors (multiple times)

- Leaving the freezer open overnight (once)

- Leaving the stove on after cooking (once)

These incidents escalated as isolation progressed. Particularly concerning were the serious household failures clustered in September, toward the end of withdrawal. While safety mechanisms averted catastrophe, the realization was terrifying: My awareness and actions were misaligned. Operating unconsciously—and committing potentially life-threatening errors—instilled profound fear.

This prompted reflections on future risks, including those associated with aging. With diminished social access in later life, individuals with traits like mine may face substantially elevated daily hazards.

This fear yielded one tangible outcome: At the end of September, I commenced blogging. This represented the sole concrete achievement from my two months of isolation. It was not pursued as a leisure activity but as a preventive measure against peril.

As someone with a background in the humanities, I have always found joy in writing and self-expression. While the feeling of the "fog lifting" did not occur immediately, the internal suppression I felt was certainly alleviated. When I am lost in my own thoughts and worries, the pressure in my heart builds up like a pressure cooker, making it difficult to cope. Writing provided a vital release for that pressure.

Conclusion: Navigating Post-Isolation Challenges

From this experience, I derived several insights:

- Compounded Physical Decline and Easy Fatigability: Regular exercise alone cannot offset the fatigue accompanying social reintegration; the burden post-isolation exceeds expectations.

- Stress as Essential Stimulation: Isolation-induced stimulus deprivation leads to cognitive fog and severe behavioral failures; maintaining basic human functioning necessitates a degree of social interaction (and its attendant stress).

- Crisis as Catalyst for Output: The progression of failures fostered a sense of urgency, culminating in blogging as a means of cognitive restoration.

Most crucially, I wish to convey to those currently enduring hardship: Ending isolation does not equate to immediate recovery. Even after reengaging with the program in October, fatigue, cognitive decline, and recurrent failures continued. Healing demands time.

Thus, patience is paramount. Embrace small steps: A single walk today suffices. Completing laundry counts. Even one "turn" per day is adequate. Reducing goal scale amid limited energy is not a shortfall—it is a strategy for safety.

Do not gauge recovery by pace or output. Assess it by persistence and the choice to endure. If you stand at isolation's threshold—or are emerging from it—you need not demonstrate prowess. Proceed gradually. Safeguard yourself.

At times, survival manifests as a modest advance—and that is sufficient. If this narrative alleviates isolation or eases pressure for even one individual, its purpose is fulfilled.

Thank you for reading this article.

If you found this article helpful, interesting, or relatable, would you consider supporting my survival and activity?

You can support my survival challenge through two ways:

1. U.S. Amazon Affiliate: If you are outside Japan, or prefer another way to support me, please click my Amazon link below. It doesn't matter what you buy; simply clicking the link and purchasing any item on Amazon helps sustain my life. I will be genuinely grateful for any commission received.

2. Japanese Banner:Please click the support banner below (Japanese ad). Every click contributes approximately one Japanese yen to my necessary living funds.

Purchase on Amazon here (Sorry. Image not displayed)

Crystal Geyser, Alpine Spring Water Natural, 30pk